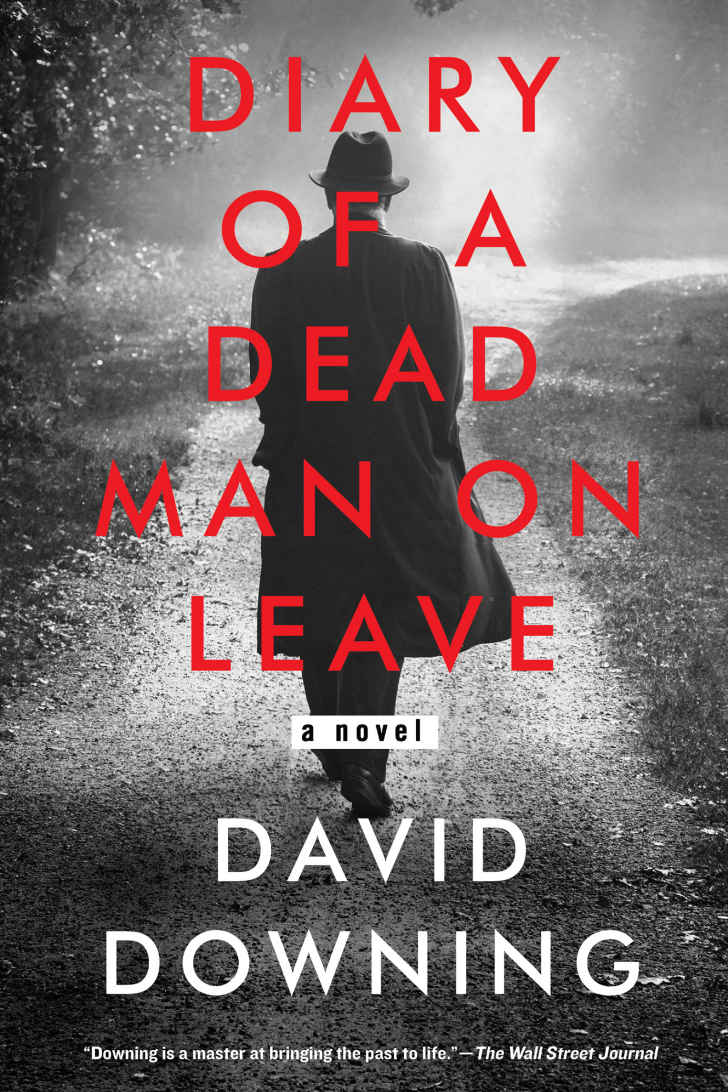

This is the Manaus Opera House today.

When my brother flew 900 miles up the Amazon in the early 70s with his French Belgian girlfriend, they were on the trail of ideas for a movie. Her father owned a film company in Brussels. The two of them had an established record of getting in anywhere they thought they would find an idea.

Manaus Opera house was abandoned and growing derelict at that point. My brother J. wanted to see the performance spaces. She insisted they go directly to the attic. I presume they must have taken a flashlight. (It was long before iPhones with a light app.) The attic had crates and chests of papers and documents. That is how F. found the idea for her next film, which eventually won first prize at the Rotterdam Film Festival. What interested my brother were bills of lading that showed the women of Manaus in the 1890s shipped their table cloths, sheets, pillowcases and other expensive linens down the Amazon River and across the Atlantic to England or Portugal to be laundered in non-Amazon water and returned. By the 1890s, faster ships took less time than they had earlier, as little as 15 days, but the trip down the Amazon had to be added in. It seems to me that even with a laundress as efficient as Lila at my local laundromat – Lily once carried six bags of laundry half mile to her shop, quick stepping all the way – the Manaus linen would have been away for two months.

No problem. Manaus was the center of a rubber boom. Most rubber at this time was coming from the far-east plantations grown from seeds stolen from the Brazilian jungles. Rubber plantations couldn’t grow in South America because of leaf blight, but the rubber plant -the hevea tree – could grow in the jungle, a tree here and a 20 minute jog away, another one there.

It was very time-consuming work, but that was not a problem. The rubber men had guns and thugs. They rounded up the natives and offered them jobs. The native men had wives and children. They considered the guns and thugs and were convinced to take the job. First they had to buy the kit – three months supplies of food, clothing and equipment to tap the ‘weeping trees’. Everything was of poor quality and priced high. Then there was the cost of transportation by river. Getting there through rapids and waterfalls was half the fun. By the time, he arrived at camp, the worker owed $150.

He was on a two-year contract, Soon he would have to take out another loan. Poor pay meant that he never came near to paying the first one.

Every day the trees had to be tapped anew, beginning before dawn, a slog through the jungle from one tree over a long trail to the next. Three hundred in total. A few hours latter, the cans had to be emptied into a pail. In the afternoon, the rubber had to be cured by rolling it into a ball and heating it in smoke. This process took 3 hours and by the end the ball weighed 200 pounds. Five centavos for a kilo-2.2 lbs. Twenty-five lbs at that rate earned 11.4 centavos.

Wade Davis in One River is my source. I am grateful to my fellow-Canadian for his documentation. Perhaps, like me, he considered trying to relate centavos to the dollars of the time, but gave up because he didn’t trust his research.

The boss expected more than the 25 pounds the worker could produce. Punishment was excessive. Men would be kept chained up for a year at a time. Dying was no escape, for then your family had to pay your debt, so your son would be drafted into the rubber biz and your daughter sold into prostitution.

A literal stable of daughters was a useful device for breeding new workers. These new people grew up tough, subject to whippings and unspeakable abuse. It was a kind of experiment in survival of the fittest. The first paragraph of page 239 of One River describes cruelty that has put me off lunch.

Meanwhile in Manaus, things were different. Even the laundry was cared for.

On dazzling white, stiffly ironed table cloths, dinners costing as much as $100,000 were served on the best imported China and eaten with sterling silver. The caviar was Russian, the champagne French, the butter Danish, English meat, German potatoes, Belgian pickled vegetables. (Brother J. has not introduced me to those delicacies.) The guests were seated at tables of Carrara marble on chairs of cinnamon and cedar shipped from London. The gentlemen would retire, not to the smoking room, but to one of a dozen elegant bordellos and choose from a menu ($400 for a 13-year-old Polish virgin/ $8000 for the desirable lady who showered in iced champagne her clients could lap up). Jewels were acceptable payment. Manaus was the world capital of diamond consumers. Of course, $100 bills were used to light cigars. Of course, horses drank champagne from silver buckets.

Eduardo Ribeiro, the governor of Amazonas laid out cobble-stoned boulevards, cobbles from Portugal, still the colonial power. The roads were lined with ornamental trees from Australia and China. He saw to it that Manaus had the first telephone system, a race track, many schools,hospitals, churches, banks and a Palace of Justice, which cost $2.5 million. He installed water filtration, an electric grid for a city of a million, and a large streetcar network when the population was only 40 K.

His crowning achievement was of course the Theatro de Amazonas, a monumental Beaux Art Opera House, the focal point of central Manaus. Again ironwork from Glasgow, marble and gold leaf from Florence, crystal chandeliers from Venice, 66,000 tiles from Alsace-Lorraine, murals of the jungle, painted in Europe and shipped back, total cost a mere $2 million.

Opening night, January 6, 1897, the Grand Italian Opera Company performed La Gioconda. Rumor is that the Opera House was built to entice Caruso to sing there. Apparently, it worked. “Operating expenses included subsidies of more than $100,000 a performance, the cost of luring established performers across an ocean and a thousand miles up the Amazon to a lavish venue in the midst of a malarial swamp” (Davis p. 235).

The opera house was refurbished in 1990, closed after one performance – residents who got squeezed out by tourists rioted- and opened finally in 1997. A new symphonic orchestra saved it.

Seems like the background for a novel, probably a mystery

In my novel, I Trust You to Kill Me, set in 2121 in Colombia, the main character Alena wonders aloud to Santiago, a whiskey priest, why there has been so much cruelty in their country.

“I’m thinking of writing a book called The Dead of Colombia.” She shakes her head. “The indigenous people, all the dead from the civil wars, the drug cartel dead, all the sea-rise dead and now all the dead from raiders. Escobar had 46,000 killed in Medellin alone. It would be a big book. And the bodies — the bodies ended up in the Magdalena River, eaten at by vultures. Where does the murder and cruelty come from, Did we Spanish bring it with us?”

“We eat too many peppers, probably. We drink too much guaro. We take too much cocaine,” says Santiago.

“Maybe it’s just the heat and the mountain coffee,” she says. She wanted to sound ironic but she only sounds sad.