This is Blake’s house. Still Blake’s house, although you can’t see him sitting on his third floor balcony, reading the Toronto Star and drinking coffee.

To be precise, it is the house of the estate of Blake Durant, one good reason why you can’t see him sitting in his lounge chair with his coffee near at hand, cursing Donald Trump and angrily refolding his paper

It is, in fact, the house that I have just sold. For the full asking price, modest enough when you consider it is on a Cabbagetown street full of million dollar houses, but large enough to make my eyes bug out. From it, you could walk to work in Toronto’s financial district. You could park one car in the attached garage and another in the driveway. You could enjoy a private backyard deck with lovely small trees.

First, you would want to spend another $150,000 redoing the floors, installing HVAC, including duct work and upgrade the two four piece bathrooms. You might want to redo the windows and the kitchen. But the people who bought Blake’s house have that handled. The family just bought and reno’ed the almost identical house attached to the south.

I got just under $900,000. Blake and I had owned two houses as a married couple and we struggled to get $180,000 for the last one in 1979, the one under the hill, with the pool and the big family room, the gardens, the dry stone wall, the den, and the finished basement, on a cul de sac in leafy Scarborough. An ideal place for children to grow and a brisk walk to a commuter train downtown. You get the picture – our dream home, rendered mausoleum by divorce and teenagers who pissed off in its wake.

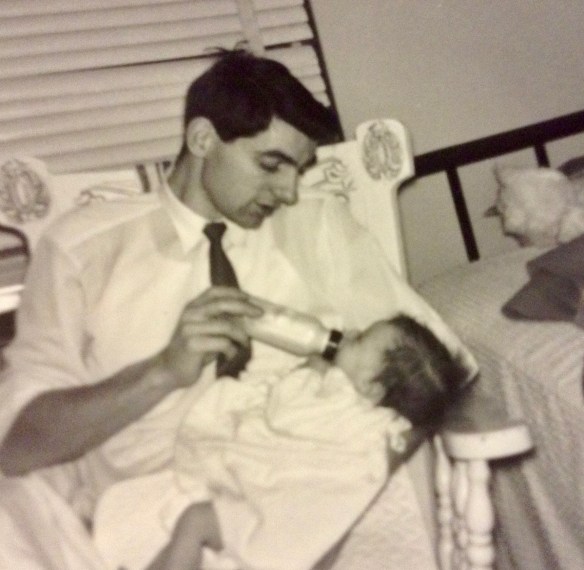

And yes, I am both ex-wife and executor. I even volunteered. Frankly, I didn’t trust Blake to protect our children’s interests and he didn’t have any friends that I trusted either. The other thing is that I loved Blake, indeed I love Blake.

That’s a problem.

Having sold the house, I feel as if he’s died all over again. When the deal closes at the end of August, I suppose I’m in for a third Blake death.

A few weeks before he passed, he confided that he was leaving me a terrible mess. He cried. He was in bad shape then, wasting away, wracked with pain and on heavy meds, but Blake always cried easily. He wasn’t exaggerating either. The mess both physical and financial was spectacular.

Five of us set about clearing things up, six if you count Alice who took herself bag and baggage back to the apartment Blake had been paying for for years. With our encouragement. After she left, the place was somewhat less like a hoarder’s paradise. It took six weeks. Waste Management sites in Toronto and Mississauga saw a lot of us, as well as Value Village. Much furniture changed hands at the curb. Some valuables on Kijiji. From time to time, one of the other of us lost hope and had to be invalided out for a few days.

“That place sucks the joy out of you!” one of us declared.

Plus it smelled of pee. It smelled badly of pee. There had been cats. There had been a very old dog. And there had been an incontinent patient. It took a professional, an industrial cleaner, an ozone machine and $3000, not to mention 11 Febreze units to get the air to the point where we could be there without every window and door wide open.

The garage was a horror show all on its own. Got Junk wanted thousands to take its disordered contents away. The only male member of our quintet threw himself at it with all his pent up rage at his father. Weekend after weekend, he dragged stuff out and off-loaded it. One guy, much to his wife’s chagrin, became the new owner of 8 bookcases and a teak table with four chairs. The childhood train set – Blake’s really – fetched $200. The last thing to go was the Bhau Haus sofa which Habitat for Humanity insisted would never go out the door – although it had come in there 25 years before. Blake’s son got it out. Like his father, he understood leverage and angles. He towed it to the curb and it went away.

Afterwards when there was nothing left to do, he found himself grieving.

Grief is a bitch. It ambushes you. Just when you think you’ve got it handled, it smashes you back down. Just when you think you’re too annoyed and overwhelmed by Blake’s lack of responsibility to care that he’s gone, you discover that your heart feels different.