Is it possible to change the future? If it is, is it wise?

Is it possible to change the future? If it is, is it wise?

First, you would have to know the future needs to be changed, I suppose. You might have a strong sense that the immediate future is not going to go well as a friend of mine did as she listened to a buzz bomb overhead in 1942 during the London blitz. She heard the telltale silence announcing the bomb was about to hit and prayed very hard that it would miss her and her infant son. It did. It landed on a house in the next street, killing another mother and her baby.

(Did she change her fate? Certainly, she thought she did and still suffered over it 60 years later.)

You might have received a prediction that you believe to be true. It is hard to disbelieve an oncologist and even your future-telling Aunt Mae can have a convincing track record. The latter believed that the only reliable way to change fate is to change character, an infinitely harder task than waving a wand. People do outlive their doctor’s prognosis, often by making drastic changes and summoning up reserves they did not know they had but most people are disinclined to make such fundamental changes or so Aunt Mae said.

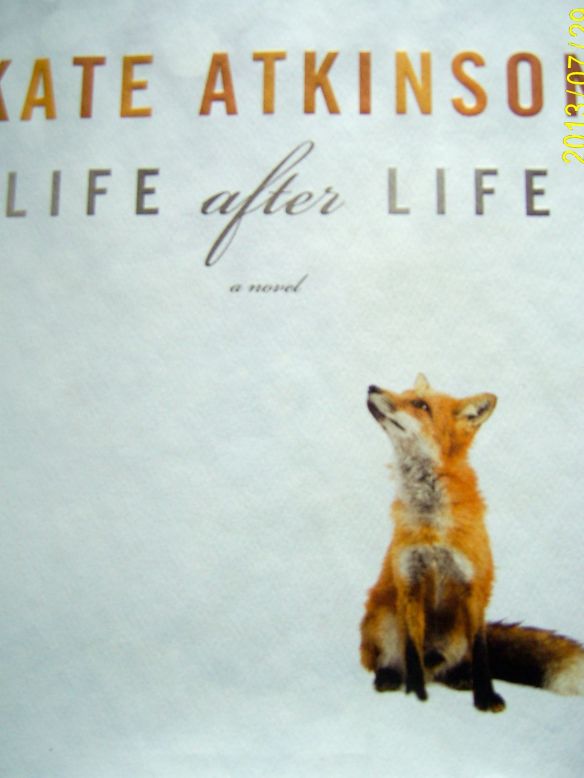

Ursula Todd, the protagonist of Life After Life by Kate Atkinson, dimly senses her past-life misfortunes and tries to avoid them. Past lives’ misfortunes would be more accurate. She is, for example, born several times on February 11, 1910 always to Sylvie and Hugh Todd. The first time a snow storm prevents the doctor’s arrival. She does not even take a breath. “Darkness fell.”, we are told as we will be many more times. The next time Dr. Fellowes gets there and cuts the cord that is around her neck. There are 8 chapters all called “Snow” that describe Ursula’s birth day. Eventually, even her irritatingly numb mother, Sylvie, has figured out that she needs to keep scissors in her night table drawer.

Some reviewers have, erroneously, suggested that Ursula is reborn into the next life at, say, 16, the point at which the subsequent narrative begins. This is wrong. Kate Atkinson explained in an interview with Eleanor Wachtel on CBC Radio 1 (available as a podcast, CBC app free) that Ursula starts over on February 11, 1910 in each case: it’s just that so much repetition would have bored readers.

The earliest opportunity Ursula has to change the future occurs at the end of the First World War in 1918. Bridget, the Todd’s maid, goes off to London for the celebration and brings the Spanish Flu home to infect Ursula and her beloved little brother, Teddy. Darkness falls. Next time, Ursula has a vague presentiment that Bridget should not come into the house when she comes back and tacks a note on the kitchen door and locks it. Sylvie outwits this plan. Next time, Bridget ends up with a sprained ankle but hobbles, gamely, off to London. “Darkness and so on.” By this time, Ursula is learning what déjà vu is, but Slyvie tells her not to dwell on “these things”. The Irish Bridget is more sensible, declaring that Ursula has second sight. For her thanks, this time, Ursula pushes her downstairs and finally prevents the Spanish Flu from carrying off Teddy and of course herself.

Sylvie takes Ursula to a Jungian therapist, who has not treated a child before but turns out to be eminently qualified. He teaches Ursula such Buddhist ideas as that of the eternal return, of dying and being reborn. And he accepts her strangeness.

But Ursula’s returns are not about learning to be a better person through lessons of retribution in successive lives. They are about getting things right, so that at least some of the harm life can do gets mitigated. The opening chapter in which 20 year-old Ursula takes her father’s Webley pistol to a Berlin cafe where she meets the Fürhrer for tea and struesel, for example, just might have prevented World War II.

This is one of two death-and-misfortune scenarios that she repeatedly tries to correct: death by bombing or attendant war trauma and sexual assault when she is 16.

The sexual assault by her older brother’s American friend on her 16th birthday initially leads to dire results, including loss of her mother’s affection in every iteration and death at the hands of an abusive husband in one. Gradually, however, Ursula perfects her punch

World War II is a more complex problem. Initially, Ursula is haunted by a feeling of flying out a window. She is living in London in November 1940, enduring nightly German bombing raids. Night after night presents an opportunity for “darkness” to fall. Initially, she lives in the same flat on Argyll Rd., sometimes still in a relationship with a high level man from the Admiralty, sometimes not, but in every life the place gets bombed and the residents killed. She might be in the basement shelter or upstairs, retrieving someone’s knitting, but her life ends there. Finally, we come to a life in which she is an air raid warden, no longer living in a flat on Argyll Rd. but attending to its bombsite. The baby Emil, who had driven her crazy crying, is now part of the debris she stumbles over doing rescue and recovery.

But the Germans are not just the enemy. Ursula’s cousin, Izzie’s son, given up for adoption in one life, has been adopted by a German family and is of an age to be flying a bomber over London. In another life, Ursula has made yet another bad choice in husbands, marrying Jurgen while she is travelling in Germany. In one life, the mother in the family that she stayed with introduces her to Eva and in another she sets out to befriend a woman in a photo shop who turns out to be Eva Braun and so gains an entré to Hitler and the Berg, Hitler’s mountain retreat. She is invited there by Eva when her daughter, Frieda, becomes ill. At the end of the war, we watch as Ursula and Frieda starve in bombed out ruins in Berlin. That chapter ends with the observation that she had never chosen death over life before.

Then as a kind of muscular solace we are treated to Ursula, back in London, an air raid warden. Gradually, her obsessive thoughts and compulsions have shaped her choices so that she has avoided her own death, but she has witnessed many others. The detail and realism of these chapters is astonishing and makes for a rousing climax.

As the author says, there is never really a moment when Ursula sees clearly what is going on, but in “The End of the Beginning”, she does gain a measure of clarity. She has learned to shoot a gun by the way. Finding herself in a sanatorium, she observes to her psychiatrist that time is a palimpsest. The canvas can be painted over again and again. She has wasted precious time, but now she has a plan. And she knows that she must “become such as you are, having learned what that is”.